Ecological and cultural histories

In societies with oral rather than written traditions, ecological and historical information is embedded in many different forms of oral tradition (Wehi et al. 2019, Wehi 2009). In this research, I and my collaborators explore some of this ecological information, what it tells us about past ecosystems and how it acts as a blueprint for living.

Whakataukī

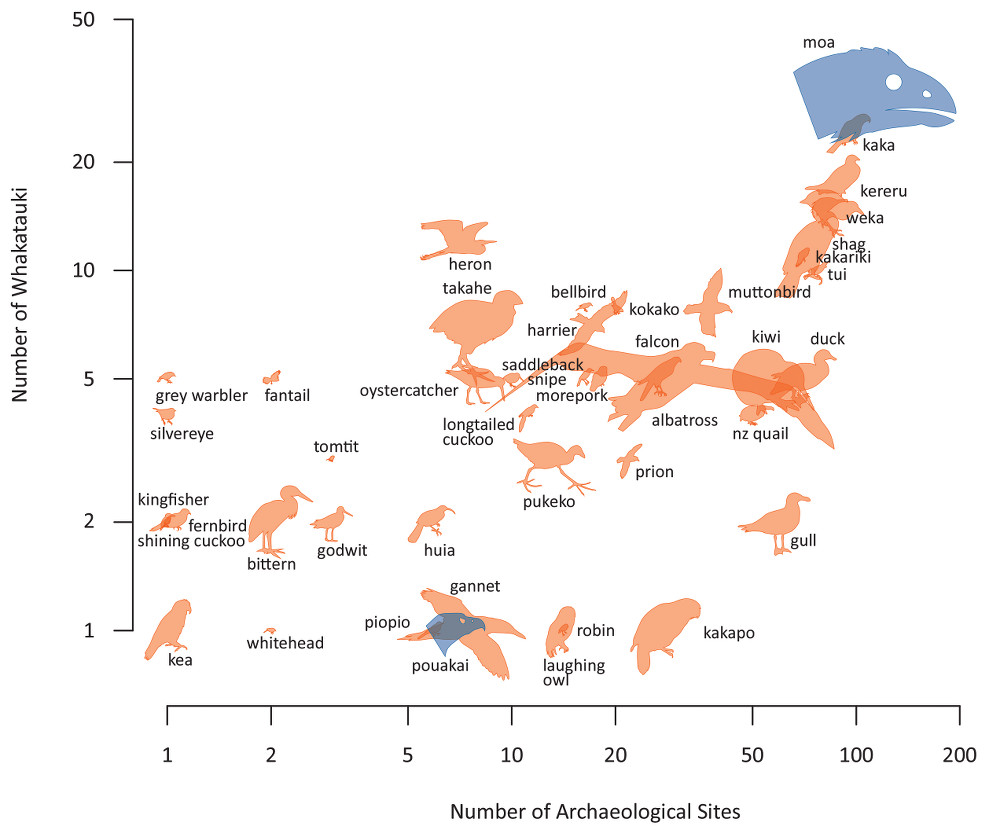

Extinction of keystone fauna was important for shaping ecological and social thought in Māori society, and suggests a similar role in other early societies that lived through megafaunal extinction events.

Extinction of keystone fauna was important for shaping ecological and social thought in Māori society, and suggests a similar role in other early societies that lived through megafaunal extinction events.

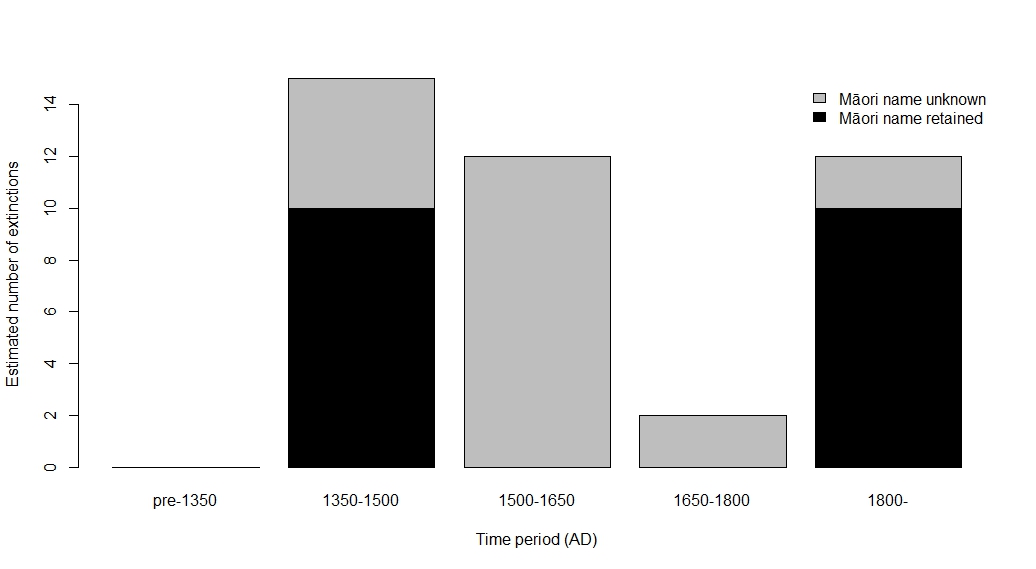

Most avian extinctions on mainland New Zealand occurred either prior to AD 1500 (within 150 years of Māori arrival), or after European arrival, post-1800 AD. With bats as the only living terrestrial mammal, birds were critical to both ecosystems and human survival.

Māori names for birds that became extinct prior to European arrival are now unknown, with the exception of words for moa and pouākai. This loss contrasts with the retention of names for birds that became extinct after European arrival, and highlights one way that language and knowledge of biodiversity are intertwined.

Key avian extinction periods occurred shortly after Māori and European settlement periods; invasive mammal arrivals have been identified as important drivers of extinction, along with overhunting after Polynesian arrival and habitat destruction after European arrival. See more on this work here and here.

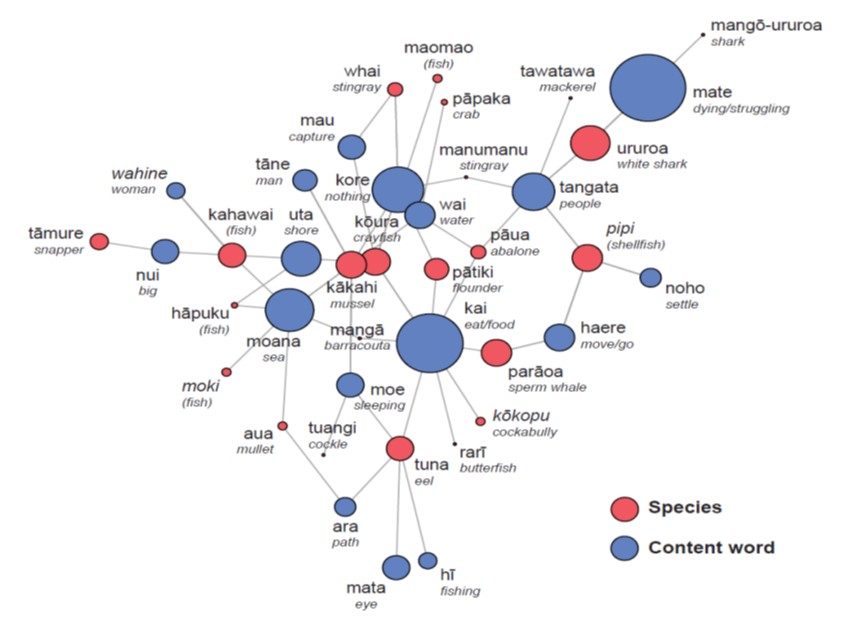

There is a great diversity of knowledge embedded in oral tradition. In work on marine and freshwater species, we created a network of high frequency species names and content words appearing in individual whakataukī (e.g. kai and kōura, food and crayfish; kai and pātiki, food and flounder). The resulting network (shown below), indicates clear connections between sharks, and death (mate) with humans (tangata), indicating a strong relationship between their behaviour (i.e. struggling to death, persistence, perseverance) and desired human attributes in times of confrontation.

Relationships between tuna (eel) and kai (food), watchfulness and sleeping, suggest the importance of alertness and observation when fishing. The proximity of fish species and the network to moana (ocean) and uta (towards the shore) gives examples of spatial proximity, or the different habitats where these species may be found. The network links between wai (water) and shallow water species (e.g. pāua, pātiki, pāpaka (abalone, flounder, crab)) and kai (food) but also to mau (capture) and whai (pursue) to illustrate further examples of food sources, and spatial proximity in relation to to harvesting actions

This short video tells the story of the Māori name for Tūi bird.

References

Wehi PM, Carter L, Harawira TW, Fitzgerald G, Lloyd K, Whaanga H, MacLeod C 2019. Enhancing awareness and adoption of cultural values through use of Māori bird names in science communication and reporting. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43 (3): 3387. 10.20417/nzjecol.43.35

Wehi PM, Cox MP, Roa T & Whaanga H 2018. Human perceptions revealed by linguistic analysis of Māori oral traditions. Human Ecology 2018: 1–10. 10.1007/s10745-018-0004-0

Whaanga H, Wehi PM, Cox MP, Roa T & Kusabs I 2018. Māori oral traditions record and convey indigenous knowledge of marine and freshwater resources. NZ Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 52: 487–496. 10.1080/00288330.2018.1488749

Wehi P, Cox M, Roa T, Whaanga H 2013. Marine resources in Māori oral tradition: he kai moana, he kai mā te hinengaro. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 2(2): 59–68. 10.1016/j.imic.2013.11.006

Wehi PM 2009. Indigenous ancestral sayings contribute to modern conservation partnerships: examples using Phormium tenax. Ecological Applications 19:267–275. 10.1890/07-1693.1.

Wehi PM, Whaanga H & Roa T 2009. Missing in translation: Māori language and oral tradition in scientific analyses of traditional ecological knowledge. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 39: 139-149. 10.1080/03014220909510580

McAllum PM 2005. Care and development of pā harakeke in 19th century New Zealand: voices from the past. Journal of Māori and Pacific Development 6 (1): 2-15.