Plant harvesting and cultural use

Everywhere in the world, humans and the natural world depend on one another in many complex ways and in many cultures, humans are seen as part of nature. This research examines how climate change may threaten the connections between people and their kin in the natural world, on whom we rely. We show that combining plant distribution data with human cultural information can help us plan for the effects of climate change on these relationships.

Everywhere in the world, humans and the natural world depend on one another in many complex ways and in many cultures, humans are seen as part of nature. This research examines how climate change may threaten the connections between people and their kin in the natural world, on whom we rely. We show that combining plant distribution data with human cultural information can help us plan for the effects of climate change on these relationships.

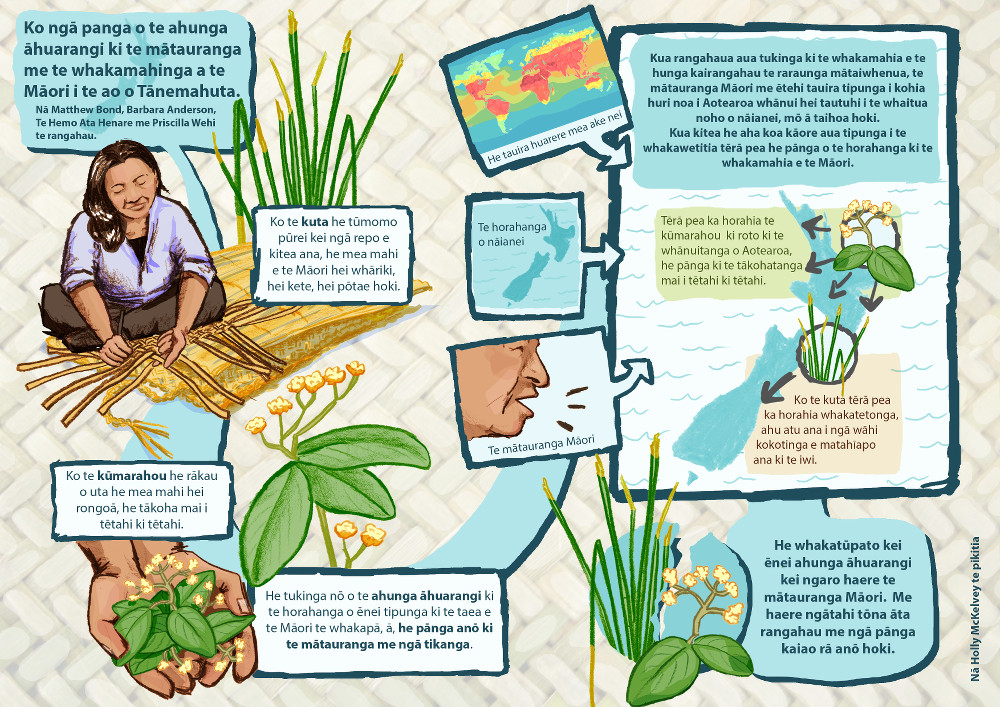

We focus on two plants that are used for weaving and medicine, because they are important to the history and identity of the Indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. First, we made maps of where the two plant species currently grow, based on where scientists have collected samples in the past. We next used computer models of future weather patterns to make maps of where the species are likely to grow in the future under climate change. Finally, we combined the current and future maps with information about where people currently harvest these plants and how important these harvesting places are.

We focus on two plants that are used for weaving and medicine, because they are important to the history and identity of the Indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. First, we made maps of where the two plant species currently grow, based on where scientists have collected samples in the past. We next used computer models of future weather patterns to make maps of where the species are likely to grow in the future under climate change. Finally, we combined the current and future maps with information about where people currently harvest these plants and how important these harvesting places are.

Our results show that there are still places where the climate will be suitable for these plants to grow in the future. However, these plants will be less likely to grow in many places where they are most important to people for weaving and medicine. This means that although the plant species themselves are not threatened by climate change, the human knowledge, history, and use of these plants is in danger. This potential loss would have ramifications for Māori culture on regional and national scales. This project shows how we can use models as a first step to protect the relationships between organisms and the people who harvest and interact with them from the impacts of climate change.

Collaborators: Te Hemo Ata Henare is one of Northland’s treasures and an expert weaver. Matthew Bond visited New Zealand on an EAPSI fellowship, and completed his PhD in 2020 from the University of Hawai’i. Barbara J Anderson specialises in conservation planning and ecological climate modelling. We also particularly thank Tautoro Marae, Northland weavers, and Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa. He mihi nui.

This research has been covered in the following articles:

– Climate change threatens Māori plant use and knowledge

– How climate change could throw Māori culture off-balance

– Climate change threatens Māori plant use

– Effects of climatically shifting species distributions on biocultural relationships

Matthew Bond, one of the researchers on the project published this article on the Student Blog of the Society for Economic Botany which included the video made during our fieldwork.

In the main publication that resulted from this study we translated the abstract into Māori. Research materials published in Māori are often difficult to find and therefore we included the abstract in Māori from this paper below.

Rāpopotonga

He wāhi nui nō ngā Iwi Kāinga, Iwi Taketake hoki ki te tiaki i te kanorau ā‐ao o te koiora, o te ahurea. Heoi anō kāore anō kia tau te whakaahua i te horahanga o te momo koiora ki te whakauru i ngā tirohanga ā‐Iwi Kāinga, ā‐Iwi Taketake ki ngā haukotinga i ngā hononga o ngā tikanga ā‐Iwi Kāinga, a‐Iwi Taketake. He hāngai tonu tā mātou titiro ki ētehi momo hirahira ki te Ao Māori, ka matua tirohia ngā taurangi matapae o ngā whaitua oranga o ia momo. Whakamahia ai e mātou ngā tauira horahanga ā‐momo (SOMS) he whakatau tata i te horahanga rāpea o te wā (1961–1990) o ia momo mai i te kōpae takahanga me ngā taurangi matapae, kātahi ka hangaia he mahere mō te arotau ā‐ahurangi o te wā e heke mai nei. Kei ā mātou whakatauiratanga te kitenga ko te arotau ā‐ahurangi o tētahi momo he nuku whakatetonga mai i ngā rerekētanga o te pāmahana me te whakatīwharatanga; ā ko tā te momo tuarua he haere whakateraki, tuatahi mai i te kaha kē ake o te pāmahana. Ki te tūhonotia tahitia ēnei whakatauiratanga ki te mōhiohio o ngā rohe me ngā tikanga ā‐iwi, he kitenga tērā pea ka haukotia te wātea o ētahi koiora e hirahira ana ki te ahurea ā‐iwi. Te arotau o tētahi momo i nukuhia nuitia mai i tōna wāhi hirahira mo te raranga, ā ko tō te tuarua i whakarahia ake kia uru mai tētahi tokomaha anō o ōna kaiwhakamahi i tōna rongoā. Mai i te rereke haere o te ahurangi i rerekē haere ai ngā tūāhua o ēnei momo he pānga pea ki te huāngatanga ā‐whakapuruanga o te taiao ā‐ira tangata; ki te tūrangawaewae; ki te tuakiri ā‐ahurea; me te koi o te mārama ki te rohe me ona whanaungatanga, taea noatia te motu me ōna nā ano hoki. Ko tā tēnei rangahau he whakaahua hōu i te arotakenga o ngā whakaraerae ki te rerekētanga o te ahurangi, he tautuhi i ngā rautakinga o te takatūranga mā ngā tauira o te horahanga ā‐momo ki roto o te anga oha‐kaiao.

References

- Bond MO, Anderson BJ, Henare THA, Wehi PM 2019. Biocultural impacts of climatically shifting plant distributions. People and Nature 1: 87–102. 10.1002/pan3.15